Latest news about Bitcoin and all cryptocurrencies. Your daily crypto news habit.

In the famous Bitcoin whitepaper, published in 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto essentially solved a computational puzzle called the “Byzantine generals’ problem” or the “Byzantine Fault.” In this FAQ, we discuss what it is and how Satoshi solved it.

Throughout the history of man, people used ledgers to record economic transactions and property ownership. A ledger is often referred to as the “principal book,” and entries can be recorded in stone, parchment, wood, metal, and with software as well. Ledgers were used for centuries, but the shared ledger system became really popular in 1538 when the church kept records.

In Mesopotamia, which was about 5,000 years ago, scientists discovered Mesopotamians used single-entry accounting ledgers. Much of it was complex and these ledgers accounted for things like property and money. But with a single-entry ledger, all anyone has to do is remove one line of entry or a few lines, and the funds would be gone or disappear from the records.

Double-entry ledgers

During the Renaissance period, intelligent people discovered double-entry bookkeeping, which literally changed everything in the world of accounting. Our modern financial system is based on the double-entry system created more than six hundred years ago. Double-entry systems grew because trade swelled beyond borders, so people needed a way to maintain records that were far more trustworthy than the single-entry accounting ledgers. Leveraging single-entry accounting would not work well when dealing with people who are thousands of miles away.

The double-entry system was first documented centuries ago by Luca Pacioli (1446–1517), a mathematician and Franciscan friar. Towards the latter part of the 15th century, this system became extremely popular, as it was leveraged by merchants and traders everywhere. Now double-entry bookkeeping isn’t necessarily transparent and these types of books can be private or open. The system does a much better job than single-entry accounting when it comes to errors, fraud detection, and financial reality. But most mathematicians and economists understand that the double-entry system can be manipulated.

So the double-entry system allows an entity to record a total of what is owed and what is owned (Assets = Liabilities + Equity). Alongside this, double-entry accounting keeps a record of what the entity spent and earned. Traditionally this system has two corresponding and equal sides that people call “debit” and “credit.” Historically, people often use the left side for debit entries and the right for credit. One of the biggest issues with the double-entry system is trusting the human and fallible bookkeeper, messenger, or accountant. Moreover, in today’s world of monetary finance, double-entry systems are used regularly, but the world’s central banks are far from transparent or based on financial reality.

Triple-entry ledges and the Byzantine generals problem

When computers came around, ledger systems became far more advanced and people tried to push the double-entry system to the next level. Triple-entry accounting was first conceived in the early eighties and the inventor of the Ricardian contract, Ian Grigg discussed the method well before it was solved. The problem with creating something more advanced than the double-entry accounting system was the notorious “Byzantine generals problem.”

The “Byzantine generals’ problem” or the “Byzantine Fault” in a nutshell

In essence, the Byzantine generals’ problem is an allegory in the field of computer science, which tells a story of two generals (there can be more than two generals) planning to attack an enemy city. The generals tell both armies to attack from each side of the enemy’s castle, the east side and the west side. The issue at hand is a timing or synchronization problem coupled with trust, because both armies need to attack simultaneously. Now the two generals split a group of messengers but the only way the messengers can communicate is by entering via the enemy castle. The Byzantine generals’ problem is not being able to trust the message from the messenger, as it may not be valid or truthful.

Basically, when a distributed ledger is being shared among computing systems people cannot trust which system or server (node) is trustworthy, compromised, or functioning with a failure to detect. However, on October 31, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous person(s) which created Bitcoin, released the Bitcoin white paper that solved the Byzantine Fault dilemma. Nakamoto wrote an email to the Cryptography Mailing List which said:

I’ve been working on a new electronic cash system that’s fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party — The main properties: Double-spending is prevented with a peer-to-peer network. No mint or other trusted parties. Participants can be anonymous. New coins are made from Hashcash style proof-of-work. The proof-of-work for new coin generation also powers the network to prevent double-spending.

The Bitcoin white paper published on October 31, 2008.

The Bitcoin white paper published on October 31, 2008.

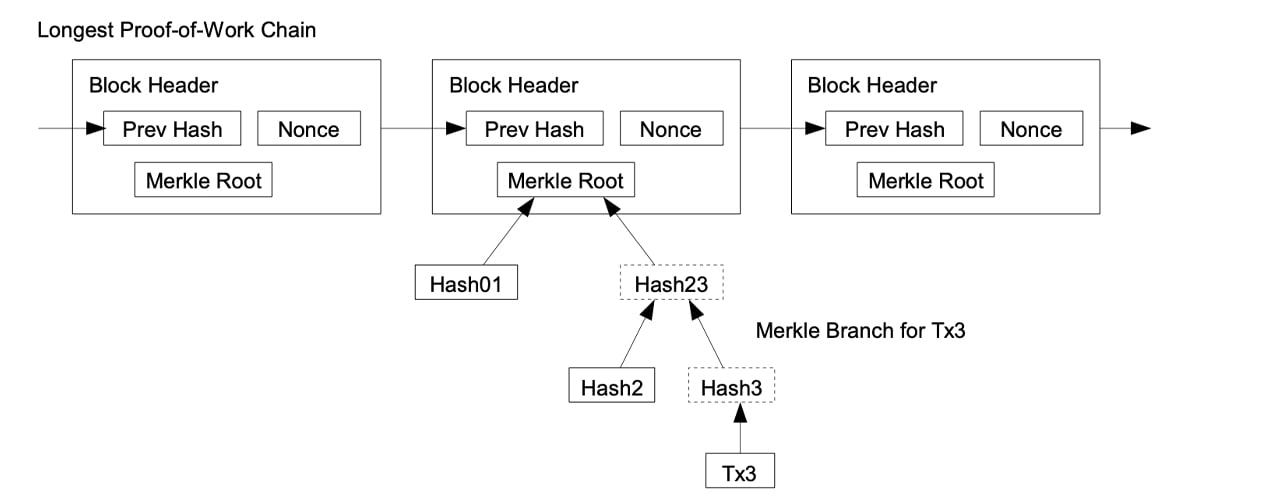

Basically Nakamoto invented the triple-entry accounting system or essentially gave the theory life. Triple-entry bookkeeping is far, far more advanced than the traditional double-entry systems we know of today. Essentially all the accounting entries are cryptographically validated by a third entry by hashing and a nonce.

“Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending,” Nakamoto’s infamous white paper says. With the triple-entry bookkeeping system, the entries (transactions) are both congruent, but the infrastructure also adds a third entry into the ledger’s validation process, which again is cryptographically sealed.

What is Hashing and what is a Nonce

Fundamentally, hashing or cryptographic hash function (CHF) is a mathematical function of arbitrary size we call a “message.” A nonce is an arbitrary number that is used one time when the message is concealed in plain text. In the Byzantine general tale, one army sends a message (CHF) over to the other general with a nonce. The other general then must decipher the CHF, with some partial knowledge cryptographers call a “hash target.” All the general has to do is hash the CHF and the nonce, as well as make sure everything corresponds with the hash target (partial knowledge). If everything is valid, the two generals have easily synchronized the timing of an attack, without having to doubt the message system or messengers.

Satoshi’s white paper also said:

Proof-of-work also solves the problem of determining representation in majority decision making. If the majority were based on one-IP-address-one-vote, it could be subverted by anyone able to allocate many IPs. Proof-of-work is essentially one-CPU-one-vote. The majority decision is represented by the longest chain, which has the greatest proof-of-work effort invested in it. If a majority of CPU power is controlled by honest nodes, the honest chain will grow the fastest and outpace any competing chains.

Bitcoin mining facility.

Bitcoin mining facility.

Nakamoto’s software leverages the Hashcash system, which bolsters the security of the underlying infrastructure by utilizing cryptographic hashes. Hashcash is used for Nakamoto’s proof-of-work (PoW) which is basically a blob of data that is difficult, expensive, and painstaking to produce. However, PoW is also undemanding when it comes to verifying and satisfying the agreement, as long as everyone follows the rules. There are a number of PoW schemes available like Quark, Scrypt, Blake-256, Cryptonight, and HEFTY1, but Nakamoto’s Bitcoin leverages SHA256.

It is “near” impossible or extremely hard to falsify, destroy or edit one or a few lines in the constant SHA256 ledger system. As the proof-of-work continues to build, it becomes extremely expensive and very time consuming to attack. There are other ways that networks can use to come to consensus, like the popular proof-of-stake consensus (PoS) systems. However, PoS has not proven itself as the most reliable system (security-wise) yet in order to come to consensus.

The advantages of triple-entry bookkeeping are huge, and the sky’s the limit when it comes to this relatively new technology. Triple-entry accounting offers a concept that is “near” trustless, if we remove trusting the autonomous system. Auditing, reconciliation, and transparency are all reconsidered notions when it comes to “trusting the books.” Satoshi told people on numerous occasions that he solved the Byzantine generals’ problem. “The proof-of-work chain is a solution to the Byzantine generals’ problem,” Nakamoto told James A. Donald on November 13, 2008.

Bitcoin’s inventor also stressed to Donald a few days earlier that the “proof-of-work chain is the solution to the synchronisation problem, and to knowing what the globally shared view is without having to trust anyone.”

Furthermore, the decentralized currency is pseudo-anonymous, meaning that a person can leverage as much anonymity or transparency as desired. Nakamoto explained the transparency and privacy foundations in the white paper quite well.

“The traditional banking model achieves a level of privacy by limiting access to information to the parties involved and the trusted third party,” the Bitcoin white paper details. “The necessity to announce all transactions publicly precludes this method, but privacy can still be maintained by breaking the flow of information in another place: by keeping public keys anonymous.”

Nakamoto concluded by saying:

The public can see that someone is sending an amount to someone else, but without information linking the transaction to anyone. This is similar to the level of information released by stock exchanges, where the time and size of individual trades, the “tape”, is made public, but without telling who the parties were.

The well known cryptocurrency expert, Andreas M. Antonopoulos does an excellent job explaining the tale of the Byzantine generals’ problem and how it applies to Bitcoin in the video below.

This article was originally published on Bitcoin.com by J. Redman.